Washington, DC - Where do people go when considering careers in the military? Online, of course. Based on the search terms they selected, they often found themselves on sites like army.com, armyenlist.com, and similar URLs for other branches of the service. But according to an FTC complaint against Sun Key Publishing, Fanmail.com, and related defendants, what was going on behind the scenes of those sites will surprise you. Another notable aspect of the case: the interesting remedy required by the proposed settlements.

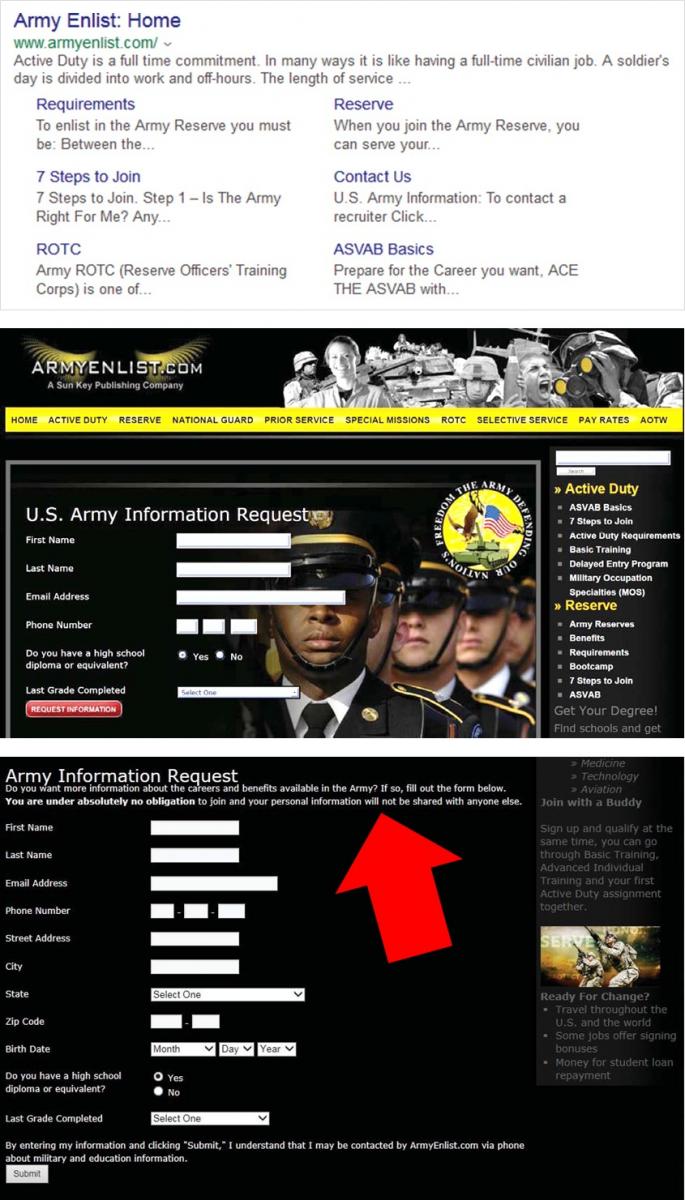

Let’s say a person typed terms like “US Army,” “Army,” or “Army Reserves” into a search engine. The screen on the right is an example of a result they might get. In this instance, one click took them to the second screen, armyenlist.com – a page featuring photos of uniformed service members and the heading U.S. Army Information Request. Once consumers filled in the fields and clicked REQUEST INFORMATION, they were taken to the third screen, which asked for even more personal data. Under the Army Information Requestheading was the promise – we’ve added the red arrow – “[Y]our personal information will not be shared with anyone else.”

Other pages used language like “Contact a Recruiter,” “Get Information About Joining,” “This is an opportunity from the U.S. Navy,” and “Are you ready to talk to a recruiter about the careers and benefits available in the U.S. Army Reserves?”

So what was really going on? According to the FTC, the webpages left consumers with the net impression they were U.S. military sites or at least affiliated with a branch of the service. In fact, the sites had no connection to the military or to official military recruiting. Instead, the defendants used the sites to induce people into turning over their personal data. Then, in violation of their own privacy promises, the defendants sold people’s personal information to companies that run post-secondary schools.

Put another way, you might think of a person considering a military career as a patriot. But from the defendants’ perspective, they were sales leads, worth between $15 and $40 each.

According to the complaint, the Sun Key defendants also violated the Telemarketing Sales Rule by placing hundreds of thousands of telemarketing calls to numbers on the National Do Not Call Registry. The purpose of those illegal calls? To make paid-for pitches for post-secondary educational services. The complaint alleges that the Fanmail defendants assisted or facilitated those TSR violations.

The FTC also challenges the content of those calls as deceptive because they reinforced the bogus military affiliation claim. For example, Sun Key’s training materials instructed their sales reps that to “decrease the number of HANG-UPS,” they should “emphasize the name of the branch and give a brief pause during the phrase delivery. ‘Hello, this is NAVY… Enlist calling for John.’” In a similarly deceptive fashion, their texts claimed to come from “Military Verification.”

Once the defendants had people on the line, they directed their sales reps to make the pivot from purported military recruiting to a school sales pitch:

I see that you would qualify to receive information on military friendly colleges, so if you were interested in continuing your education, that information could be sent along with your military information. Is that something that interests you? . . . The military supports earning a degree while serving in the military. This information can help you make an informed decision and you get the chance to SERVE, LEARN and EARN.

If the person agreed, the sales rep recommended schools that had paid the defendants for marketing leads. The FTC alleges that other promotions falsely represented that the military had endorsed specific schools.

The complaint names Sun Key Publishing, Fanmail.com, Wheredata, LLC, Christopher Upp, Mark Van Dyke, Lon Brolliar, and Andrew Dorman. Among other things, the settlements ban the defendants from misrepresenting a military affiliation and from using military recruitment to gather consumer information for sales leads. The proposed orders also mandate clear disclosures in future promotions, and put provisions in place to make sure consumers understand they’re not on official recruiting sites. What about the schools that bought consumers’ data? The defendants have to notify them about the FTC’s allegations and direct them to stop using the information.

Now to that interesting remedy we mentioned at the start. The proposed orders impose civil penalty judgments totaling more than $12 million. Based on the defendants’ financial condition, the judgments are partially suspended, but the settlements require them to turn over to the FTC some particularly valuable assets: many of the websites – including army.com, air-force.com, armyenlist.com, airforceenlist.com, coastguardenlist.com, marinesenlist.com, and navyenlist.com – that the defendants used to mislead consumers. As a result, those high-traffic sites will no longer be in the hands of a military imposter operation.

Three big-picture points to take from this case:

- Like any other government imposter promotion, sites that convey a false military affiliation violate the FTC Act.

- Companies must honor their privacy promises.

- It’s tough to come up with words strong enough to convey this message, but here goes: When it comes to deceptive practices targeting servicemembers, veterans, or civilians interested in serving their country, the FTC takes those allegations seriously. Very, very seriously.